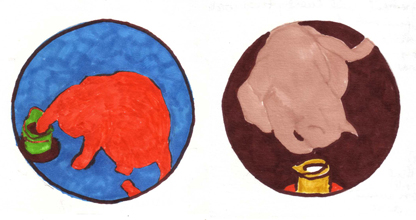

Rebecca–Trying to Draw Ashes Sneaking Milk

The other week, Gioia attended an informational lecture at her daughter’s elementary school. Many of the teachers had recently read Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck’s book, Mindset, and were excited to share her work with their students’ parents. Mindset theory, based on decades of research, examines the effect beliefs, outlook, and attitude have on achievement and success.

Dweck proposes that people with a growth mindset believe that skills and intelligence, just like a muscle, grow and develop and that success is about practice and effort. This is in contrast to a fixed mindset, a more pessimistic way of thinking about our abilities. People with a fixed mindset believe intelligence is static, leading them to avoid challenges and give up easily.

When Gioia chatted with some of the other parents who attended the lecture, one of the greatest takeaways that they identified was a shift in the way they interpreted things that weren’t going well in their children’s lives, like getting poor grades or losing a soccer game. What they had perceived as setbacks or failures were really just necessary parts of learning something new. “Failure doesn’t define you,” Dweck writes, instead, “it is a problem to be faced, dealt with and learned from.”

For a child with a growth mindset, failure might mean: “That strategy didn’t work. I need to change how I’m approaching things.” It does not mean: ‘I’m a bad person and there is nothing I can do about it.” Of course, for children or adults, failure is no fun. It can feel pretty lousy, but–and here’s another reframe–that’s a good thing, because it means we care, we are invested in the outcome. Failure then can be an opportunity, because it means a chance to learn, focus on what went well, and success tomorrow, or the next day, or the next year. Failure simply becomes information and feedback for alternative strategies-“This didn’t work, so now I need a different solution…I love making mistakes!”

So parents or anyone in any capacity in which they are encouraging others, should avoid praise that focuses on intelligence or talent as if it were a static or fixed quality, “You’re so smart!” “You’re so athletic!” Instead, we want to praise effort, or amount of work they put in: “You stuck with it!” “You challenged yourself and practiced until you got better!” “You really put a lot into this, it shows!” That’s it is OK to have to work hard and to make mistakes because this helps “build the muscles” that lead to success.

Positively yours, Gioia and Rebecca

Art directive:

Although some people are born with the ability to draw “realistically” without any training, for most people, even talented artists, it is an acquired skill that gets better with effort and training. Ask almost anyone who draws well and they will tell you they’ve put in thousands of hours practicing.

Here is a simple technique that artists use to practice drawing: pick an object you like-an apple, a stapler, a coffee cup- and try drawing the same object repeatedly, making one sketch of the same object every day for a week. Then compare Day 1’s drawing with Day 7’s. Was there any change in your skill level? We’d love to see and cheer on your efforts–snap a quick photo and email it to us–we’ll upload it to this page or post it on our Facebook Page. Show us your growth mindset in action!